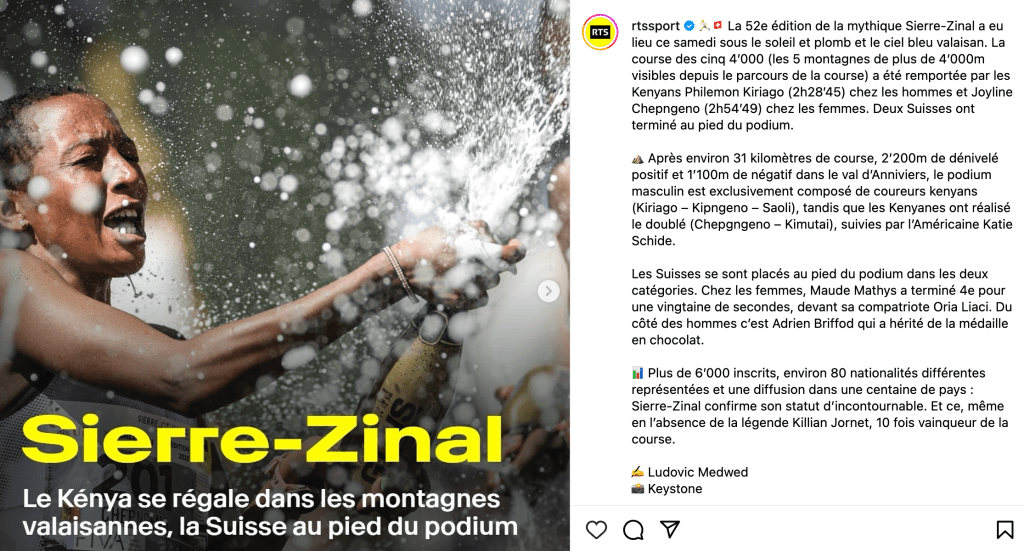

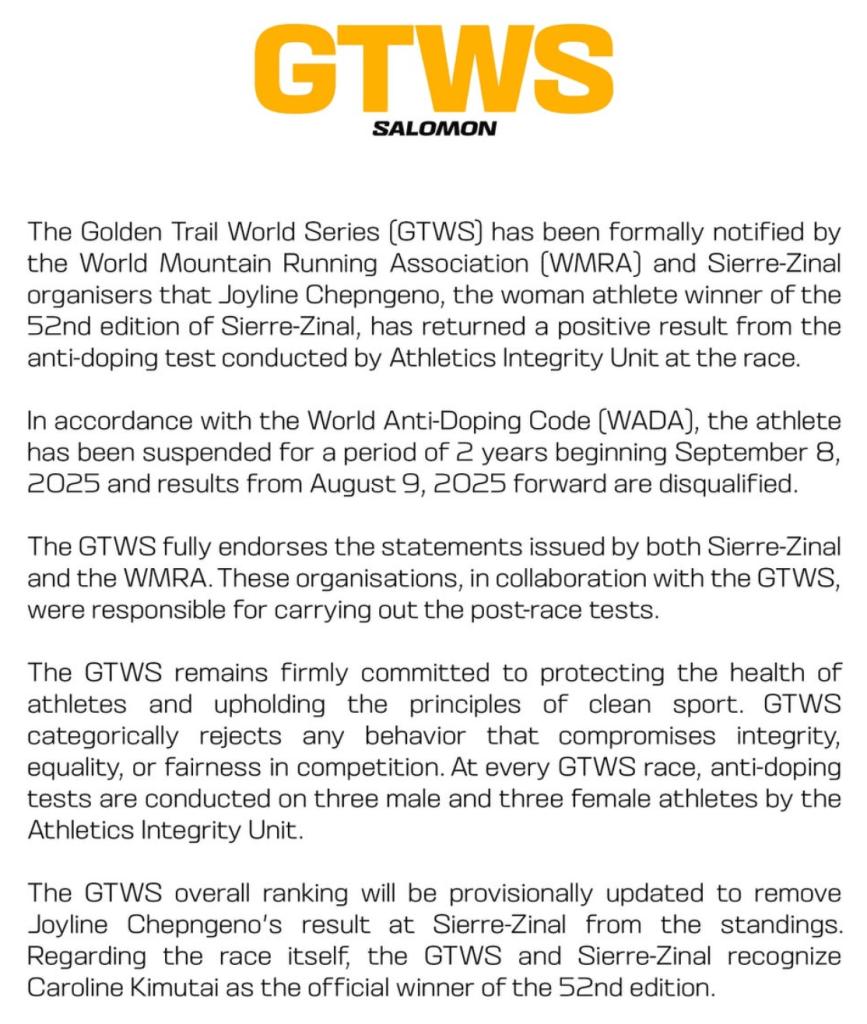

When news broke that Kenyan trail running champion Joyline Chepngeno had been banned for two years after testing positive for triamcinolone acetonide, the reactions were swift and polarised. On one side: condemnation and disbelief. On the other: questions about fairness, context, and whether the system designed to protect clean sport actually confuses athletes into mistakes.

Let me be clear, there is no place for doping in any sport, however, the Chepngeno and Angermund cases should and must make us think deeper.

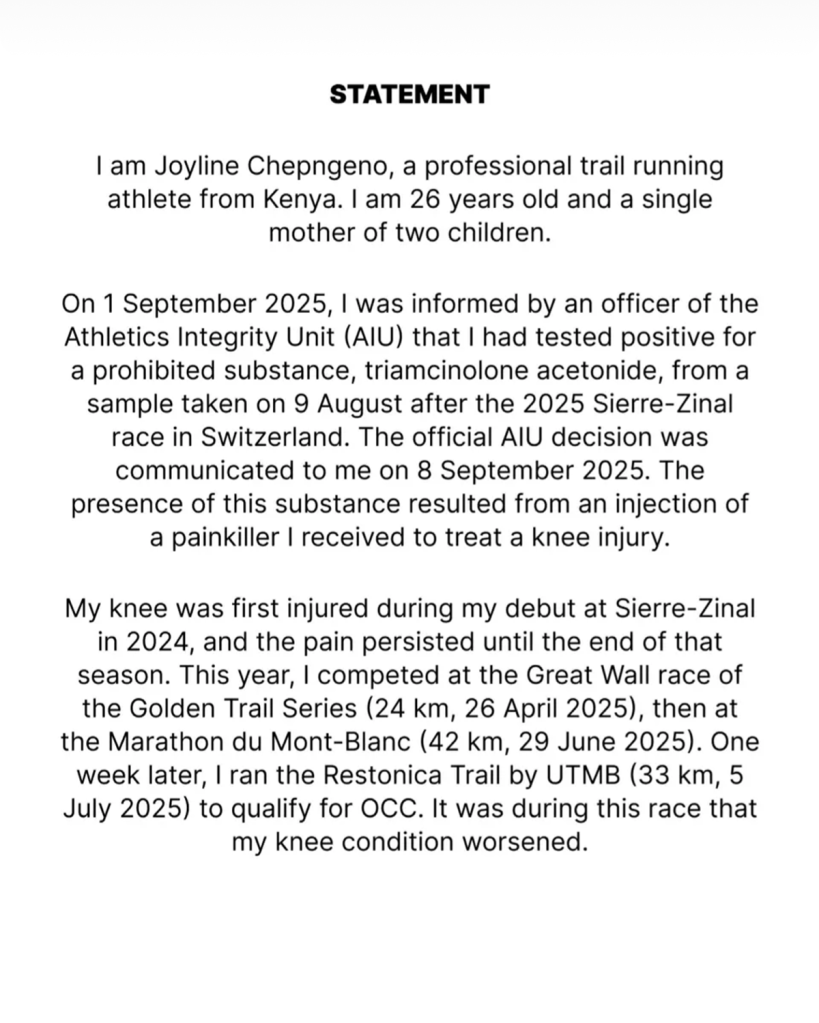

Chepngeno admitted she received an injection in July, and the drug in question – a corticosteroid widely used for inflammation – sits in one of the sport’s murkiest regulatory zones. Under the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) code, triamcinolone is banned in-competition, unless the athlete secures a Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE). Sounds simple enough, but in practice the rules are anything but. The case raises bigger questions: Was she naive? Did her team fail her? Was Salomon right to sever ties so quickly? And is WADA’s own ambiguity part of the problem?

“Chepngeno may have taken the injection for a genuine medical issue – inflammation, pain, or recovery – but without the right paperwork, timing, and guidance, it became a career-altering violation.”

Kenya’s Reputation and the Weight of History

Kenya has long been under the microscope for doping violations. In recent years, its athletes have faced increasing scrutiny, with dozens of cases making international headlines. This history frames Chepngeno’s case: even a whiff of doping from a Kenyan runner is quickly interpreted through the lens of systemic abuse, rather than individual misjudgment.

But this framing risks oversimplifying. Many Kenyan athletes operate in environments with limited medical oversight, inconsistent education about anti-doping rules, and managerial structures that prioritize racing and prize money over compliance. Chepngeno may have taken the injection for a genuine medical issue – inflammation, pain, or recovery – but without the right paperwork, timing, and guidance, it became a career-altering violation.

The Role of the Manager/ Coach: Protection or Neglect?

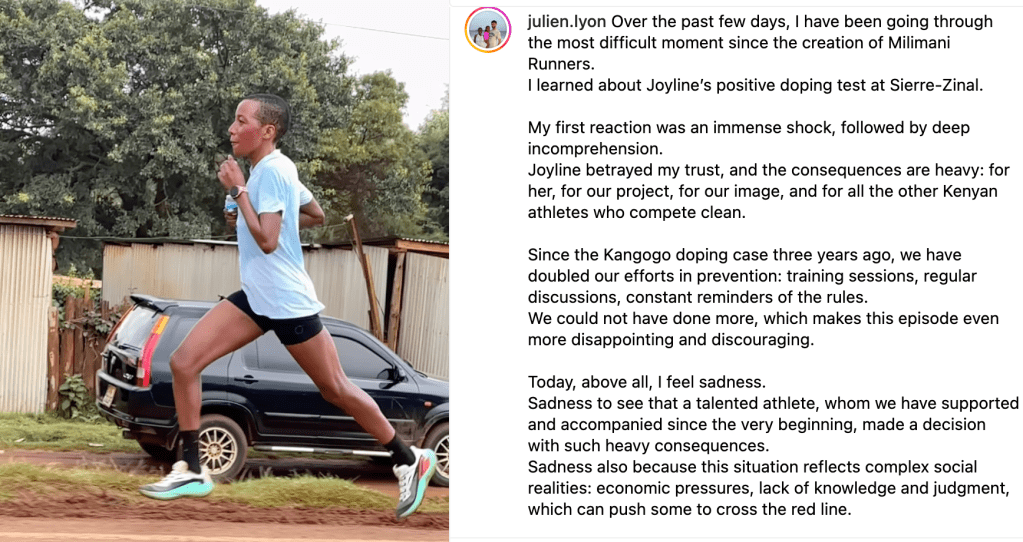

A professional runner’s manager/ coach, in this case, Julien Lyon, is more than just a race scheduler. They are, or should be, a gatekeeper for the athlete’s career:

Pros of strong management:

- Ensures the athlete understands what substances are permitted.

- Helps navigate the dense bureaucracy of WADA codes, TUE applications, and medical clearances.

- Provides financial and legal protection when mistakes happen.

- Balances competitive demands with athlete health and long-term career viability.

Cons or failures of management:

- When managers are absentee or focused solely on performance, athletes are left vulnerable.

- In many Kenyan cases, managers are foreign-based agents whose primary incentive is to get athletes on the start line, not to invest in their education.

- A lack of day-to-day oversight means athletes may trust local doctors, clinics, or informal advice without realizing the implications.

Chepngeno’s admission that she did take the injection suggests honesty, not deception. But it also signals that no one around her flagged the risk. A competent manager should have either prevented it or ensured the correct exemptions were in place. If the manager’s job is athlete protection, this could look like a potential failure? **

“The Sierre-Zinal race organisation has announced that it has banned Chepngeno’s coach Julien Lyon and his Milimani Runners team from future competitions. It has also, according to the statement, ordered Lyon to ‘fully reimburse prize money, accommodation costs and administrative fees arising from the case – including reputational harm – owed to the Sierre-Zinal Association’.” – (c) Runner’s World

Lyon also coached the 2022 Sierre-Zinal men’s and women’s champions, Kangogo and Chesang, both of whom were later suspended and stripped of their titles for doping.

In response to Sierre-Zinal, Julien Lyon via Instagram stated: “Finally, I must respond to the serious and defamatory accusations published by the Sierre-Zinal organization. These statements are completely unacceptable. I am already devoting significant energy to restoring the facts and I have no intention of giving up.” **

Update September 13th: **

Julien Lyon has responded with a clear statement on Instagram, read HERE.

Let me be absolutely clear:

• I had no knowledge whatsoever of the use of this substance.

• I have never, in any way, encouraged or tolerated such an act.

• I have always fought against doping and I will continue to do so.

From now on, I am already reflecting on concrete solutions: implementing more regular out-of-competition testing, even if it represents a significant cost that must be discussed with our partners, and developing closer, culturally adapted medical support in Kenya. I deeply regret that Joyline may have felt left alone with her pain and doubts. She had my full support, and I regret not being even more present for her during this difficult time. I want to ensure that Milimani Runners athletes feel supported not only in their sporting careers, but also in their health, their choices, and their education. – Julien Lyon via Instagram

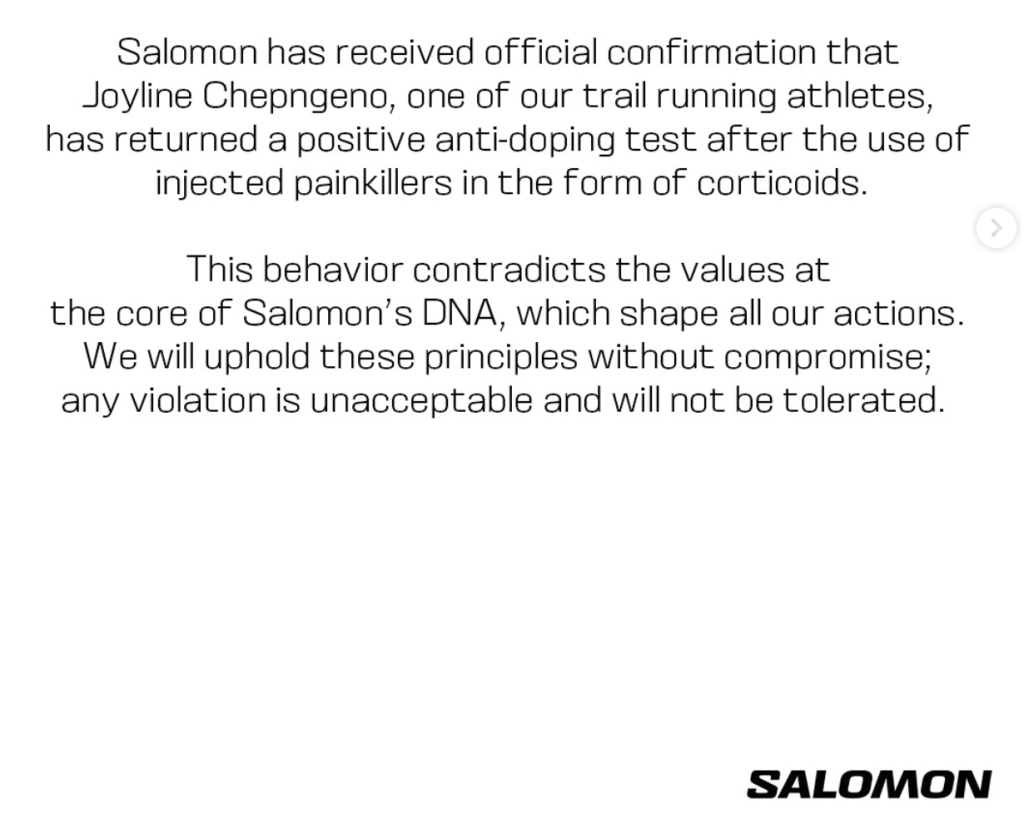

The Sponsor’s Role: Salomon’s Swift Rejection

Salomon, Chepngeno’s sponsor, moved quickly to cut ties. On one level, this is understandable: brands cannot afford reputational damage in a sport that already battles questions of integrity. Corporate zero-tolerance policies are often blunt but clear: fail a doping test, and the contract ends.

View the Instagram post HERE

But here lies the ethical dilemma. Was Salomon protecting the sport, or protecting its image? By severing ties without nuance, the brand effectively punished Chepngeno twice: once through lost income and again through public rejection. A more responsible approach might have been suspension pending investigation, or supporting her with legal and educational resources.

Sponsorship is not just about exposure and winning; it’s also about athlete welfare. When brands abandon athletes at the first sign of trouble, it signals that their investment was never truly in the human being, only in the results.

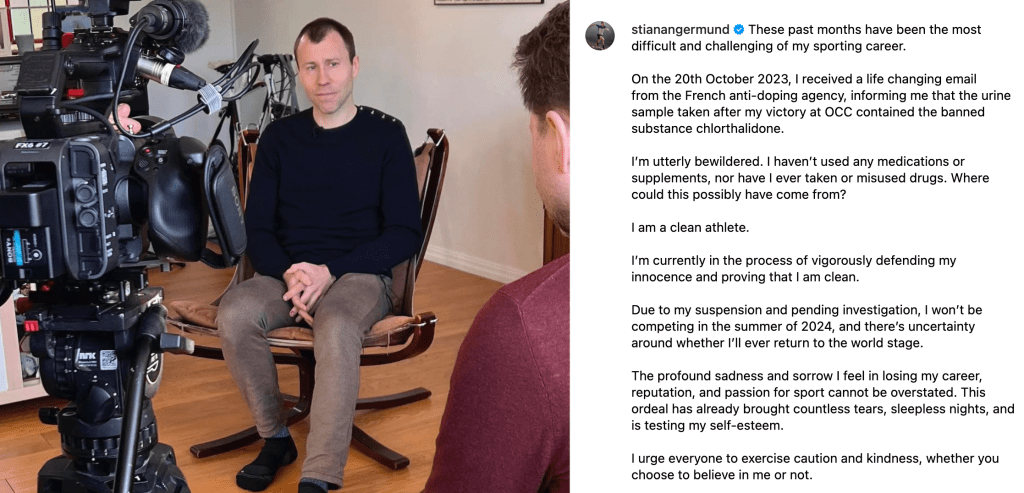

A Contrast: The Case of Stian Angermund

The difference in how Chepngeno’s case was received becomes starker when compared with that of Stian Angermund, one of Norway’s most successful trail runners. Angermund also tested positive in 2023 for the diuretic chlorthalidone.*

- *corrected for original post

Read on Instagram HERE

Yet the public response to Angermund was notably softer. Many in the trail running community rallied around him, framing him as a victim of circumstance, a clean athlete caught in an unfortunate situation. His protestations of innocence gained traction, with commentators and peers stressing his reputation, personality, and history as evidence of credibility.

On February 10th, 2024, the trail running world was rocked by news out of Norway – the two-time World Champion, Stian Angermund, had tested positive for the diuretic chlorthalidone. via Freetrail here.

Chepngeno, by contrast, has not been afforded the same sympathy. Instead, her case was quickly folded into the broader narrative of Kenya’s doping crisis, with far fewer voices offering the benefit of the doubt. This disparity speaks volumes about how nationality, reputation, and public image shape perception. Where Angermund’s case was seen as an anomaly in a clean career, Chepngeno’s was framed as part of a pattern – even though the substance she took is far more medically common, and her admission suggested transparency, not deception.

Sponsors and Double Standards

The sponsorship response reveals this double standard even more starkly. Salomon cut ties with Chepngeno almost immediately, distancing itself without nuance. In contrast, sponsors and partners in Angermund’s case were slower to act, with ‘some’ showing signs of support while the investigation unfolded. The messaging was different too: in Angermund’s case, words like uncertain, unfortunate, and out of character dominated coverage; in Chepngeno’s, the language leaned toward guilty, systemic, and Kenyan problem.

This isn’t just about corporate crisis management – it reflects deeper biases. Western athletes with strong reputations are given space to argue their case, while Kenyan athletes are too often treated as disposable. If sponsors only invest in results but not in athlete welfare, the sport risks reinforcing inequities that mirror global power imbalances.

WADA’s Ambiguity: Is Triamcinolone Doping or Not?

Here lies the central confusion. Triamcinolone is not an anabolic steroid. It is a corticosteroid — widely prescribed to treat inflammation and injury. In many medical contexts, it is routine and even necessary.

WADA bans it only in-competition, unless a TUE is granted. Out-of-competition, it is allowed. The catch? Athletes often receive injections or treatments without realizing where the “competition window” starts or ends. Did Chepngeno’s injection fall within the banned period? Did she even know the timing mattered?

And yes, I understand that the athlete has a responsibility to know and understand WADA rules.

The World Anti-Doping Code states the roles and responsibilities that athletes have in relation to anti-doping. So, athletes must: know and abide by the Anti-Doping Rules, policies and practices. be available for testing at all times.

The ambiguity sends mixed messages: if a substance is dangerous or performance-enhancing, why is it allowed out-of-competition at all? And if it is medically justifiable, why is the TUE process so opaque and burdensome, especially for athletes in countries with limited infrastructure?

Instead of clarity, WADA’s rules create traps. Athletes are told they are responsible for every substance in their body, but the system seems designed to catch technical errors as much as intentional cheats.

Was Chepngeno Naive?

The answer is complicated. On the surface, yes: admitting to an injection without checking WADA guidelines suggests a lack of awareness. But deeper down, her admission looks less like naivety and more like honesty. She did not hide the treatment, nor attempt to deny it. She took what may have been a routine medical step, unaware that it carried career-ending consequences.

The real naivety may not be hers but the system’s – assuming athletes across all geographies, languages, and economic realities can navigate a code written for those with legal teams and medical advisors.

Does Julien Lyon and Salomon have a responsibility? **

Financial and Moral Implications

For Chepngeno, the fallout is severe and many of you will say, good, that is how it should be.

- Financial: Two years off the circuit means lost race earnings, lost sponsorship income, and a gap in her career at what should be her peak. For athletes from Kenya, whose entire family and community may rely on those earnings, the consequences are devastating.

- Moral: Her reputation is damaged, regardless of intent. Once branded a “doper,” the stigma rarely fades, even if the violation was technical rather than malicious.

For the sport, cases like this erode public trust. Fans are left asking: was she cheating or simply careless? For sponsors, the financial risk increases – which in turn makes them more likely to cut ties at the first sign of trouble. And for Kenya, each case deepens the perception of systemic doping, even if the reality is far more complex.

What can be learned from this?

Contextual Justice: Not all violations are equal. Intent should matter as much as presence. Athletes like Chepngeno, who admit to treatment rather than hide it, deserve proportionate, not punitive, responses.

Clearer Rules from WADA: The line between therapeutic and prohibited must be made clearer. If triamcinolone is truly performance-enhancing, ban it outright. If it is a legitimate medical treatment, streamline TUEs and ensure athletes understand the timelines.

Better Athlete Education: Federations, sponsors, and managers need to invest in training athletes on what substances mean, how to apply for exemptions, and what to do before accepting treatment.

Stronger Manager Accountability: Managers should be held to professional standards. If their athlete tests positive due to negligence in guidance, they too should face consequences.

More Responsible Sponsors: Brands like Salomon should balance integrity with support. Cutting ties instantly might protect the logo, but it abandons the athlete. Support through due process would show real leadership.

Conclusion

Joyline Chepngeno’s ban is not just the story of one Kenyan athlete caught out. It is a case study in the tangled web of responsibility in modern sport: the athlete trying to heal, the manager who should have protected her, the sponsor that walked away, and the global regulator that still speaks in gray areas.

Was she naive? Perhaps. But more importantly, she was failed by a system that claims to protect athletes but too often punishes them for being human. Until WADA, managers, and sponsors share the burden of responsibility, athletes – especially those from vulnerable contexts like Kenya – will keep paying the highest price.

Update 12th September, Joyline Chepgneno posted on Instagram the following:

Final Note:

This article and post is designed to give a perspective to make the reader ask questions. To be clear, I am completely against doping, there is no place for doping in sport. I am well aware, for some, this article and words may make you angry – that is okay. Feel free to respond and counter with good debate and argument and be polite and professional.

** edits September 13th.

**Julien Lyon has taken exception to certain points raised in this article. Quoted below.) I stress that as a journalist, I am entitled to the right to freedom of opinion and expression, including the freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media, regardless of borders. As stipulated in article 19 in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. However, it is important to be fair and allow all viewpoints to be considered.

“Several passages mention my name and attribute facts and responsibilities to me that are inaccurate and damaging to my professional reputation. For example: – You state that “the Sierre-Zinal organisation has announced that it has banned Julien Lyon and his team” – however, I have not received any official notification of such a decision, and no sanction has legal standing at this time. – You write “this looks like a clear failure,” implying that I failed in my duty to protect the athlete – this value judgment is not based on any objective evidence and constitutes a serious attack on my professional integrity. – The phrase “Lyon has history” suggests I have a track record of misconduct, which is defamatory. I therefore request that you either: – immediately remove these passages, or – publish a right of reply that sets the record straight.”

Of course, Julien Lyon, like anyone who reads this article, has a right to reply and the comment section is open for this.

Instagram – @iancorlessphotography

Twitter – @talkultra

facebook.com/iancorlessphotography

Web – www.iancorless.com